Language of Health

The Cope Evans collection offers a cache of information that is explored through the pages of this website. This page has been created from a textual analysis of a controlled set of letters and explores themes differently than other pages, and by doing so it attempts to launch a new phase of academic study using the Cope Evans collection. Additionally, the project is grounded in familial relationships in an attempt to balance the personal nature of the collection with the academic exploration of it.

Anna Stewardson Brown, Elizabeth Stewardson Cope, and Rachel Cope Evans were three women who belonged to the prominent Philadelphia Cope-Evans family during the 19th and 20th centuries. Anna and her daughters Elizabeth and Rachel corresponded frequently throughout the course of their lives, generating a large volume of letters throughout the years, including the roughly 400 letters from the years 1870-1910 that are located in the collections of Haverford College. In addition to topics such as weather, travel, and family life, the women wrote regularly about health.

The Cope women’s discussion of health intersects with themes of gender and offers an intriguing angle for research into the Cope Evans collection. The data was coded in two steps and is represented in two sections, Symptoms and Specificity. First, the data was coded in the text as Symptoms and Unwell, and then Symptoms was further classified in Specificity. With this data it is apparent that the three Cope women discussed men’s and women’s health differently in the course of their correspondence to one another and to other family members. Although they discussed men’s health less frequently than they did women’s health, they discussed it in more specific terms by assigning men more clearly defined symptoms and known conditions. Women, although discussed more frequently in the letter collection, are discussed with vaguer afflictions.

This difference in the language of health surrounding the men and women of the family provides insight into their interpersonal dynamics. Women’s health was mentioned in the way of a general family update, whereas men’s health was reported as news primarily when the men were seriously ill or injured.

Letters written by Anna, Rachel, and Elizabeth were coded for a textual analysis to study how and when health is described. All mentions of health, data relating to family health, gender and names of those involved were coded. Two types of data captured how and when data was described, The Symptoms data includes everything that describes health such as symptoms and diagnoses. The Unwell data measure the number of times someone was described as having ill health. Both Symptoms and Unwell were classified by gender and the specificity. Although Specificity is defined in greater detail under the Specificity section, it was a way to classify the coded data to find additional trends.

In the letter collection of just over 400 letters, almost 300 of them mentioned health at least once. Many traumatic events in the family, such as the deaths of several members and prolonged illnesses were present in the letters, as well as more mundane and every-day discussions of health.

Anna Stewardson Brown (1822-1916)

Anna was born in 1822 and married Francis Reeve Cope in 1847. The couple had nine children, the oldest of those that survived childhood being Rachel Cope Evans and Elizabeth Stewardson Cope. Anna was very close to both of these daughters, and the three lived together most winters and kept in touch through letters over the summers. Anna and Francis celebrated their 60th wedding anniversary in 1907 and Francis died in 1909, followed by Anna in 1916.

Elizabeth Stewardson Cope (1848-1937)

Elizabeth was born in 1848 and was the eldest child of Francis Reeve Cope and Anna Stewardson Brown. Raised in Philadelphia and Germantown, she married her cousin Alexis T. Cope in 1875. Elizabeth and Alexis had four children, twins William Cope and Francis R. Cope Jr., Eleanor Tyson Cope, and Agnes Cope, but their son William died in infancy in 1879. The family built a home in Awbury(an estate in the Germantown section of Philadelphai) in 1882, but only a short time later in 1883 Elizabeth’s husband Alexis died of typhoid. After being widowed and losing her eldest daughter Agnes in 1899, Elizabeth spent much of the rest of her life in her home of Woodbourne in Dimock PA, frequently returning to the family estate in Awbury during the winter months. Throughout her life she was particularly close to her sister Rachel Cope Evans, affectionately called “Chellie” in their letters, and her three sisters-in-law Clementine, Annette, and Caroline Cope. Elizabeth occupied her time by hosting her children and other family members, writing letters, and later in life by visiting her young grandchildren.

Rachel Cope Evans (1850-1939)

Rachel was born in 1850 and was the second child of Francis Reeve Cope and Anna Stewardson Brown. She, like her other siblings, was raised in Philadelphia --and Germantown, taking frequent trips to Newport and other vacation spots in New England. During her lifetime Rachel was very close to her sister Elizabeth, whom she called “Lillie”. She married Jonathan Evans in 1873. They had five children, Anna, Francis Algernon, Ernest, Harold, and Edward Evans. Rachel spent much of her time vacationing, and in the winter lived with the extended Cope family at Awbury. Her daughter Anna suffered a mental breakdown and was institutionalized briefly in 1901 and she lost her son Ernest in 1911.

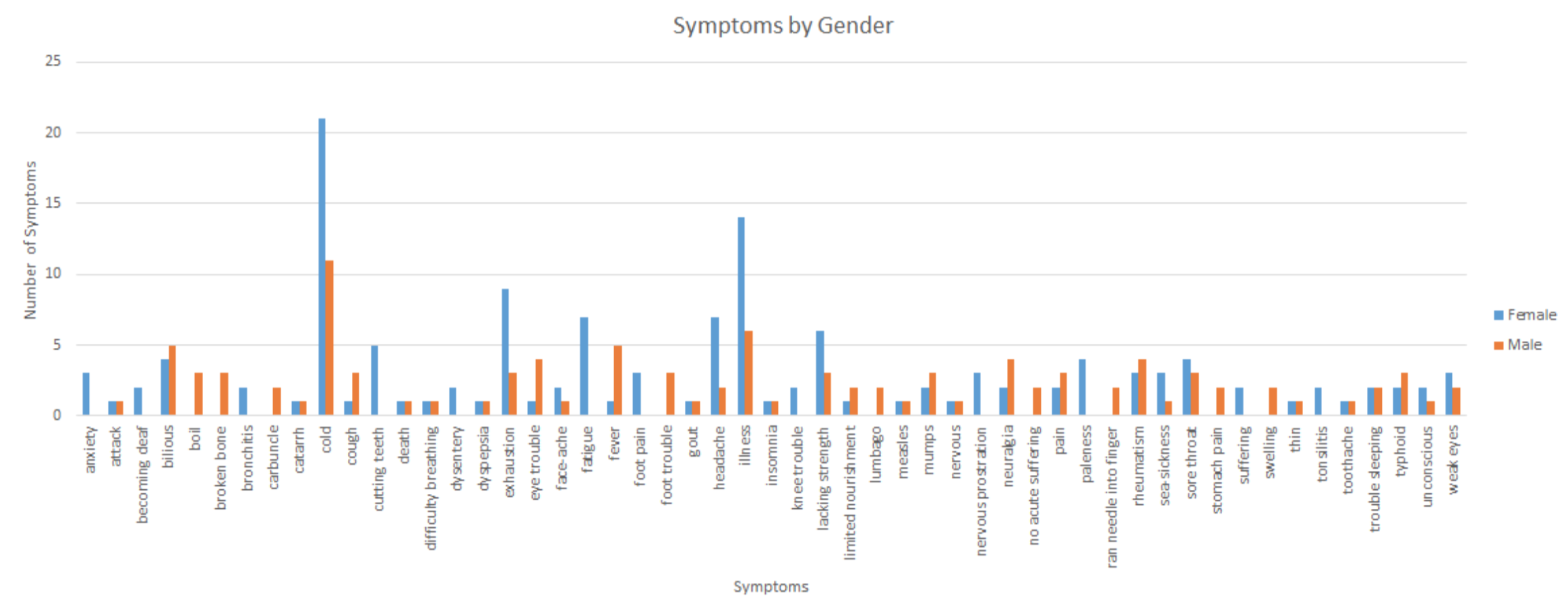

How these women describe health suggests gender differences that may reflect the different lives Cope men and women lived. The gendered language is represented by certain words which were used more frequently with women than with men and vice versa. Women were frequently described as having a cold, exhaustion, or fatigue while men were overwhelmingly diagnosed with fevers and physical illnesses. In "Symptoms by Gender" women had twice as many colds and three times the exhaustion while men had five times as many fevers and all of the broken bones. The differences in the data could be explained by the differences in daily activities.

For instance, the women lived in similar environments, often away from city life and spent more in their country estates. They tired from the heat and attributed colds to the state of the atmosphere. Their husbands and sons worked in the city and participated in more strenuous activities. This may be a gender difference in the way they thought about men’s health but it could also reflect that the men were away from the house and that was news that would interest the rest of the family. Francis R. Cope spent much of his professional life during the summer away from the family. During his retirement and declining health, he spent all of his time with Anna, and there was an increase in health related events during this time. This was a time when he was with his family for a prolonged period and therefore health was reported very regularly.

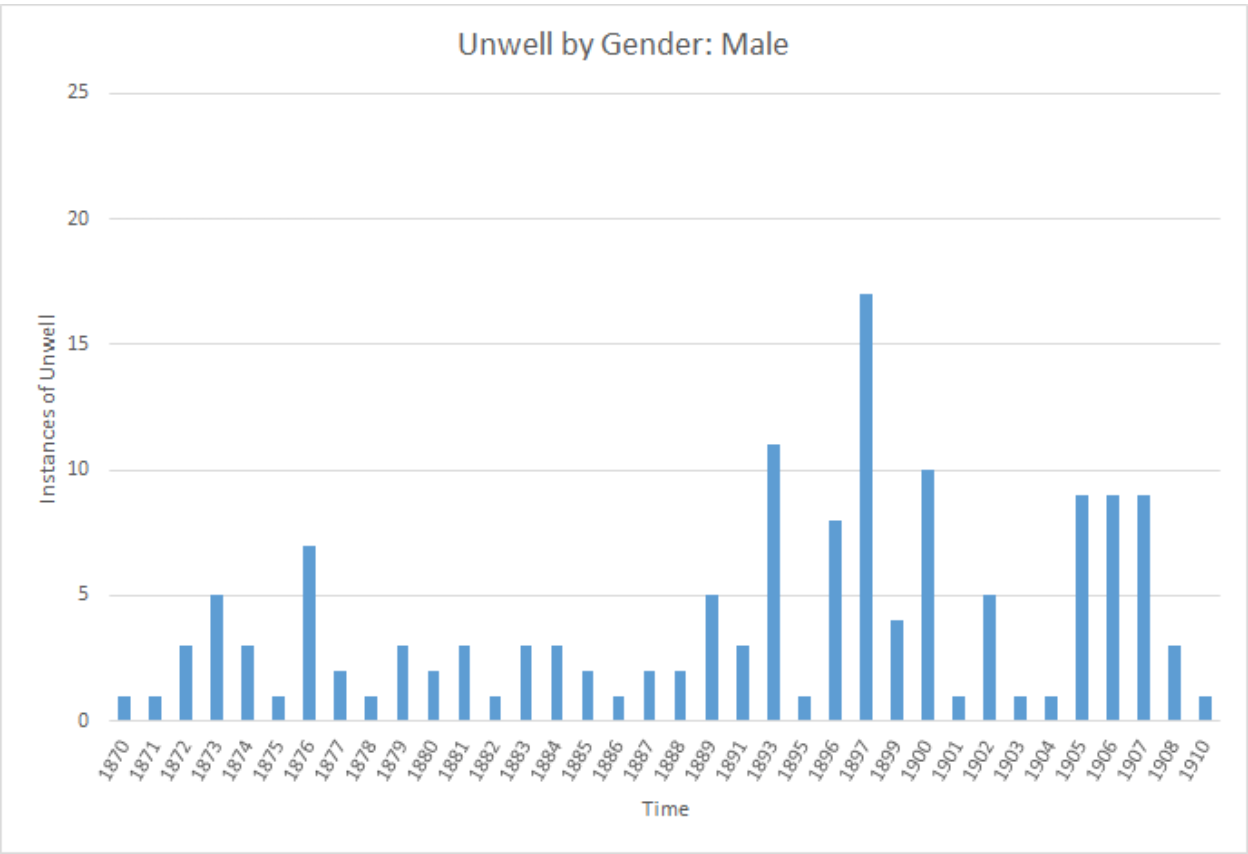

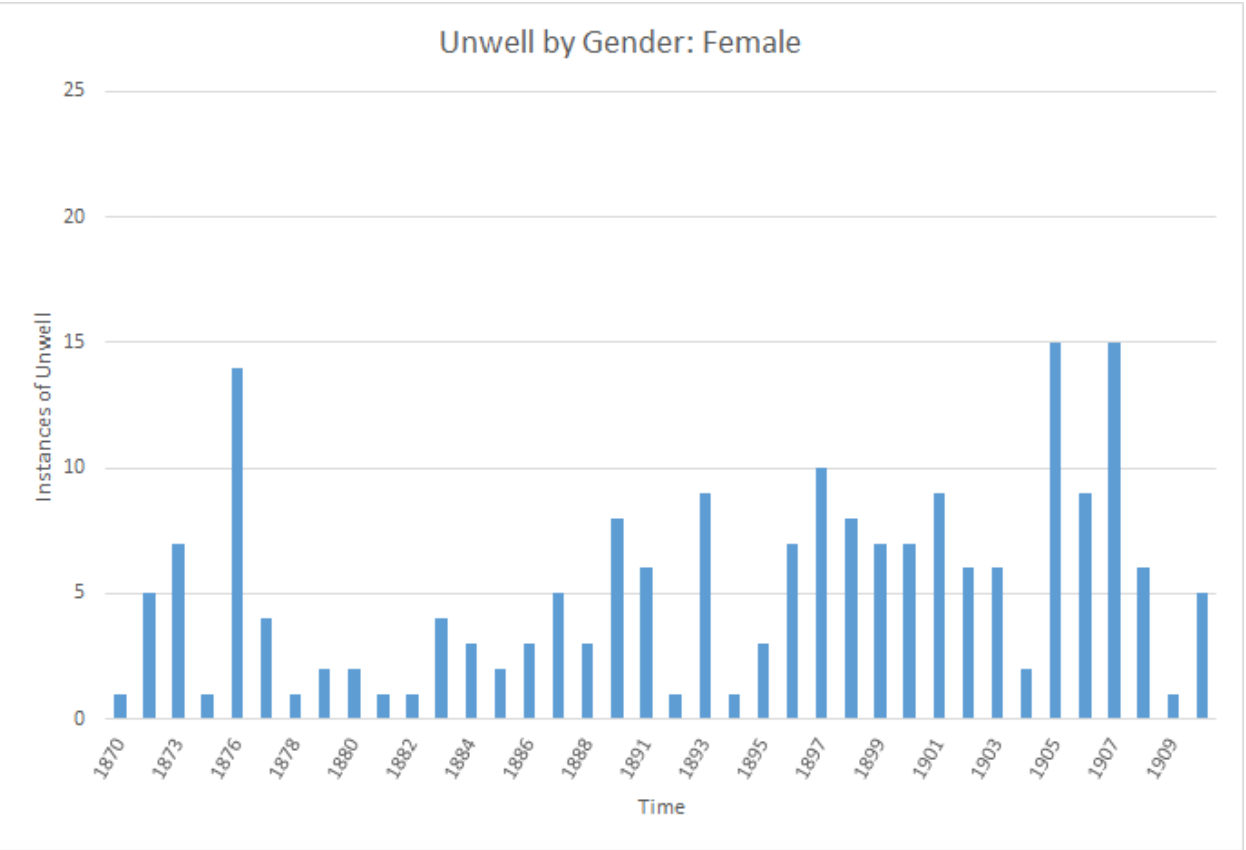

The Unwell data demonstrates how different life events brought attention to men’s and women’s health. The Unwell data measures the number of times someone is mentioned to be unwell with or without symptoms. The Unwell by Gender charts show the trends in Unwell data. They show that there was a more regular discussion of women’s health over the 40 years than of men’s.

It is proposed that women discussed other women’s health as an update, when considering both the data and the contextual information. Certain years did have higher totals and these generally corresponded with years when Cope women were giving birth. Caroline Cope Lewis had children in 1893, 1897, 1898 and 1903. Anna Stewardson Cope’s first three great-grandchildren were born in 1905-1907. These years were some of the highest totals in women’s Unwell data.

It seems like women were prompted to talk about women’s health when there was a woman recovering from her pregnancy and a newborn baby. Considering the same data, different conclusions can be drawn about men’s health. Men’s Unwell data show varying totals, which supports the idea that men’s health was shared like news only when a Cope man was ill or injured. While the women had the greatest totals in years of pregnancy, men had the largest total around declining health and death. In 1897 and 1900, Alfred Cope and Thomas P. Cope Jr. died, respectively, and they were also some of the highest totals of men’s Unwell data. Men’s declining health was often well documented. There are many letters in the early 1900s detailing Francis R. Cope’s troubles. The difference could be noticed because this particular span of years encompasses the death of patriarchs, husbands and beloved sons. The data shows that women’s health was discussed more frequently around childbirth, while men’s declining health and death were the well documented.

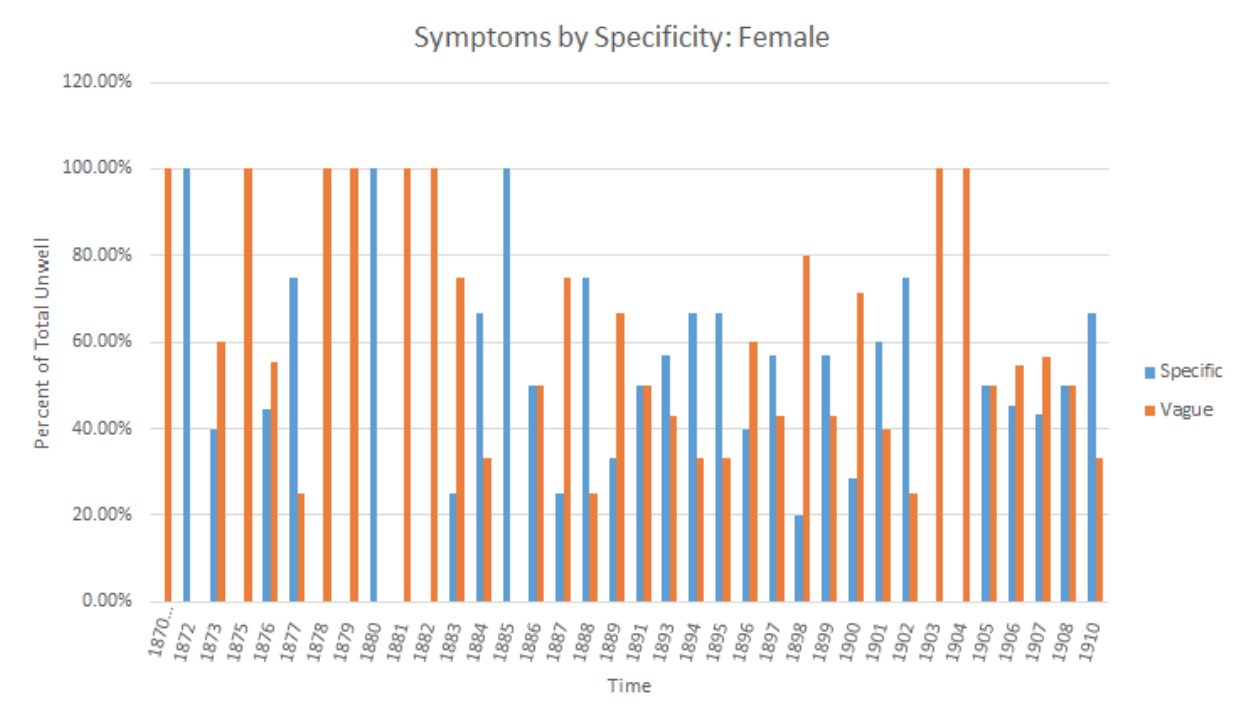

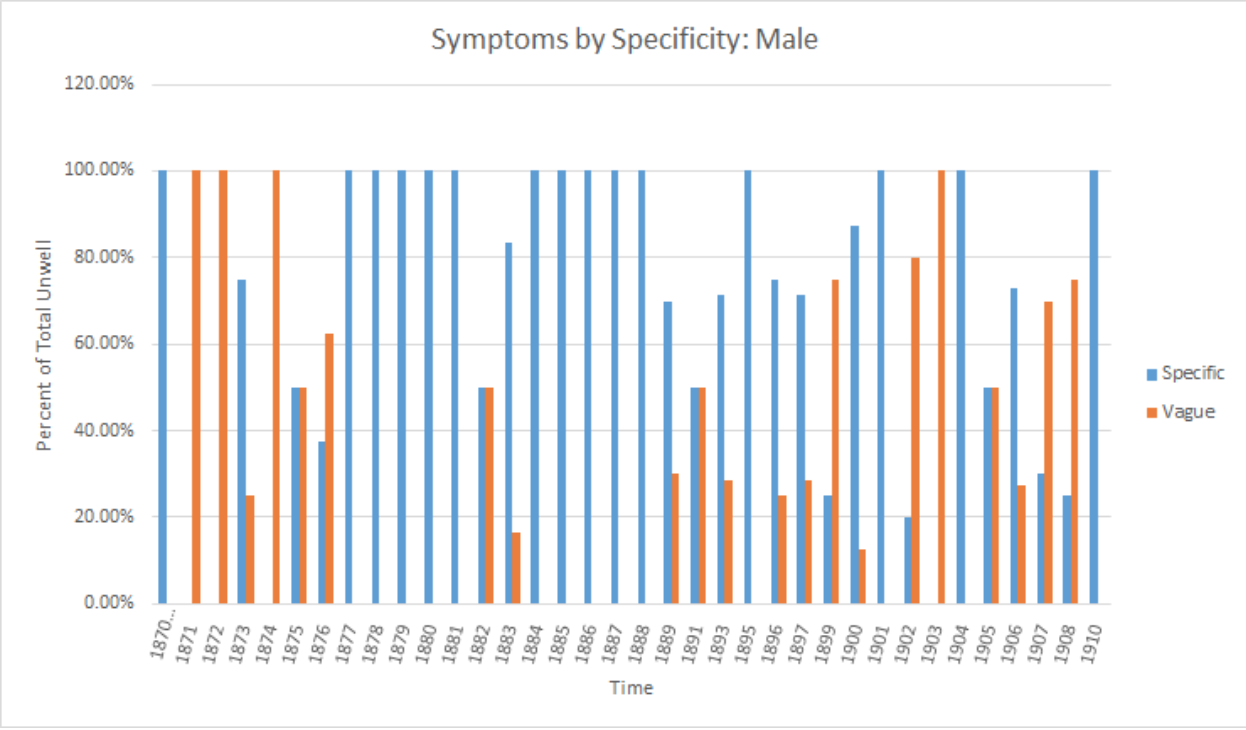

Looking at the bar chart, the proportion of specific to vagye symptoms is consistently larger when the symptoms are about the men of the family than when they are about the women. Although the men have their fair share of unspecific symptoms, it is significantly less than the women. Men are mentioned less often than women in general, but they are more likely to have specific symptoms than their female relatives according to the data set. This is an interesting trend with a variety of possible explanations. Men of this time period were involved in physical activities, such as horse riding, sailing, and sports more often than the women. The men in this family travelled extensively and worked frequently, perhaps prompting them to hide their illnesses and injuries until they had progressed far enough to become easily diagnosable. It could be that the three Cope-Evans women writing these letters worried more about the health of the men, since the men were frequently away from home, than they did about their daughters who were often in their company.

Regardless of the causes, the data shows that the men’s health is usually more specific from the beginning of the time period studied, 1870, through the end, 1910. The letter volume increases slightly, but the women do not change the way they specify men’s and women’s health. Although the world was changing around these women, their conversations with one another about the family and the family’s health are an area of consistency.

Specific or Unspecific?

Specificity was a category created during the data analysis to classify every symptom as ‘Specific’ or ‘Unspecific’. Specific symptoms were things such as typhoid fever, rashes, and boils. They were actual descriptions of an illness or specific diagnoses. Unspecific symptoms were things such as colds, fatigue, general illness, or tiredness. These symptoms did not help in understanding the condition someone suffered from and were instead vague descriptions that could be interpreted in a variety of ways. For instance, “pain” was an unspecific symptom unless it was assigned to a portion of the body, such as “foot pain”. However, “foot trouble” was unspecific because “trouble” could be interpreted in a variety of ways.

Read more about Anna C. EvansThe scholarly discussion of gender and health of the Victorian Era may be reflected in the Cope women’s discussion of health. Health in the Victorian Era has been previously studied through health reform, mental health, and a significant amount of research on the way Victorian society projected women’s health as frail and feeble (Smith-Rosenberg, 183; Stratford, 102). Much of the gender differences can be explained by the physical separation of the men and women, yet it cannot be ignored that women were frequently described by different language than men. Women were exclusively described as fatigued and overwhelmingly suffering from a vague illness such as being ‘under the weather’ and sick. Similarly, women’s health after the birth of a child was carefully monitored and documented. Women were cautioned to maintain bed rest and consider their health until months after they had delivered a child. This phenomenon could reflect an expectation projected by society that women’s health was weak, especially around sexual reproduction (Smith-Rosenberg, 185-186). Because this form of data collection and textual analysis of women’s personal writing is largely unstudied, there is no precedent for studying specificity (Winkmann). Not only does the data confirm that women’s health was consistently described in vague terms, but the discussion of men’s health often avoided vague language. Between the years 1877 and 1888, there were only two vague symptoms describing men’s health. In many ways this data reinforces the typical themes of health and gender in the Victorian Era and encourages additional research to support stronger conclusions.

Further research is needed to connect the Cope women’s letters to the greater trends in the Victorian Era. Currently the data is confined to the Cope family due to the limited number of people. While there are trends around women giving birth and men’s declining health, it would be important to find women’s letters who experienced more women’s deaths. The greater sample of women from more backgrounds could shed light into the gendering of death. Additionally, there is a window from 1877 to 1888 where men’s health only described twice with vague symptoms and several more times with vague illnesses. With a larger sample of letters, that range could be studied in greater detail for additional patterns.

The letters of Anna, Rachel, and Elizabeth were the medium through which they were able to keep in touch, maintain their relationships, and learn of their close family and friends. The language and prevalence of health, present in most of their letters, shows that health, and in particular ill health, was a subject that they were all deeply interested in and that was omnipresent in their lives. Studying the women’s letters and other personal writings offers a new perspective to study a woman’s role in society where public records may be lacking. Through the data and contextual support, the Cope women’s letters reveal that the different activities and the separation of the Cope men and women are reflected in their language of health. This wealthy and socially privileged family experienced health as one of the few traumas in their lives, and as such it is important to devote time and energy into studying it. It was important to them in their time, and therefore important to historians in ours. Further research into different families in different places and classes could add to and enhance that done with this important, but unique, family.